How to avoid overengineering

This article considers the conditions that lead teams to produce overengineered software and describes how you can avoid falling prey to such conditions.

What do we mean by “overengineering”?

When a software developer says that a piece of software is overengineered, they are saying that they think it has too many moving parts, too much abstraction, or an excessive emphasis on performance. The number of concepts required to understand the thing feels unreasonable.

It’s a fundamentally subjective call, but you know it when you see it. Like a Ferrari at a go kart race, an overengineered system is out of scale with its operating environment and intended usage.

But how does it happen? Are there certain conditions that lead teams to produce systems that observers would perceive as overengineered?

To determine this, let’s consider two stereotypical software engineering phenomena: cargo culting and a related pattern that I’ve started to call “the Xoogler effect”.

From there, we can characterize certain cognitive biases that drive a team towards overengineering.

Cargo culting

Fig. 1. The Trillion Dollar Homepage.

Fig. 1. The Trillion Dollar Homepage.

A cargo cult is a cultural phenomenon in which technologically-advanced artifacts become objects of obsessive ritual to a group of people outside of the artifact-producing society. While the term has fallen out of favor within the field of anthropology (in acknowledgement of its reductive and colonialist overtones), it’s fairly common in software circles.

To a software engineer, “cargo culting” is used pejoratively to refer to the adoption of a technology or practice based solely on its origin or popularity. Loosely, the thinking goes that if a tool, language, or convention was developed at or inspired by ideas from a large, successful company, then that tool must have contributed to the company’s success. Thus, in adopting it, you increase your odds of also succeeding.

Examples:

- “Era-defining companies like Intel and Google used OKRs, so we should too.”

- “The SRE book talks about how Google relies on service level objectives, so using them will help our services become more reliable.”

- “Most successful companies end up needing advanced load balancing and request-proxying systems to scale their microservices architectures. Our 10-person startup should adopt these systems in order to help us scale.”

Like incorporating in Delaware or only hiring graduates of name-brand universities, a particular practice correlating with notable instances of company growth doesn’t imply causation. Just because a popular or successful company uses a technology doesn’t mean that it’s appropriate or worthwhile for your situation.

The Xoogler effect

When people leave engineering jobs at big, successful tech companies, they take their former employer’s engineering culture with them. This tends to be highly valuable, for both the technical acumen of the new company and the incoming engineer’s compensation package.

But this tendency can be taken too far. The incoming employee, believing that they have a direct line to the state of the art, may go on to recreate systems in their former employer’s image to an unreasonable degree.

Not to pick on Googlers, but something about that company’s culture really brings this out. There are many notable examples of Xooglers replicating Google-internal systems and practices in the outside world, either as independent startups or efforts within existing companies. I don’t find this terribly surprising, given the tone that’s set within Google—you spend your time there constantly being told that you’re among the best software engineers to walk the face of the Earth, using technologies unmatched in their power, quality, and scalability. It makes sense that former employees feel compelled to emulate things that worked at Google1.

But this generalizes to other large and/or successful companies. Many people leave the productivity bubble of a “FAANG and friends” company and end up building tools and systems that they miss. To name but a few, this is how we got Thrift, Envoy, and three different tools based on Google’s build system.

Cognitive biases

I think these two phenomena can be linked to a handful of widely-known cognitive biases. Cargo culting is a clear manifestation of authority bias. And the Xoogler effect seems related to the law of the instrument.

It’s rational to want to stay within your circle of competence, but it can be counterproductive in excess. When you’ve been inculcated in the expert use of hammers, every problem looks like a nail. Your thinking in new environments is anchored by prior experience in old environments, which can impede learning and the development of new skills.

And it turns out that these two patterns can feed on each other. Cargo culting is catalyzed by the Xoogler effect in cases when a former big company employee’s experience is uncritically venerated by new colleagues.

How to resist the urge to overengineer

Resisting the temptation to overengineer requires one to be honest with themselves about the context in which they’re operating.

You should always design systems to address problems that are in front of you instead of falling for solutions to problems faced by big companies in the past. You shouldn’t base your company’s infrastructure on GitHub stars. And as wistful as you may be for your last company’s tools, they may not be as applicable to your current situation as you think.

Assessing cargo without becoming a cultist

When evaluating a popular tool, language, or convention, it’s worthwhile to take the time to understand the underlying forces that motivated its invention2. Before making any decisions, try to contextualize a technology within the environment that formed it. From there, you can pattern match that environment to your own in order to determine if the technology is appropriate.

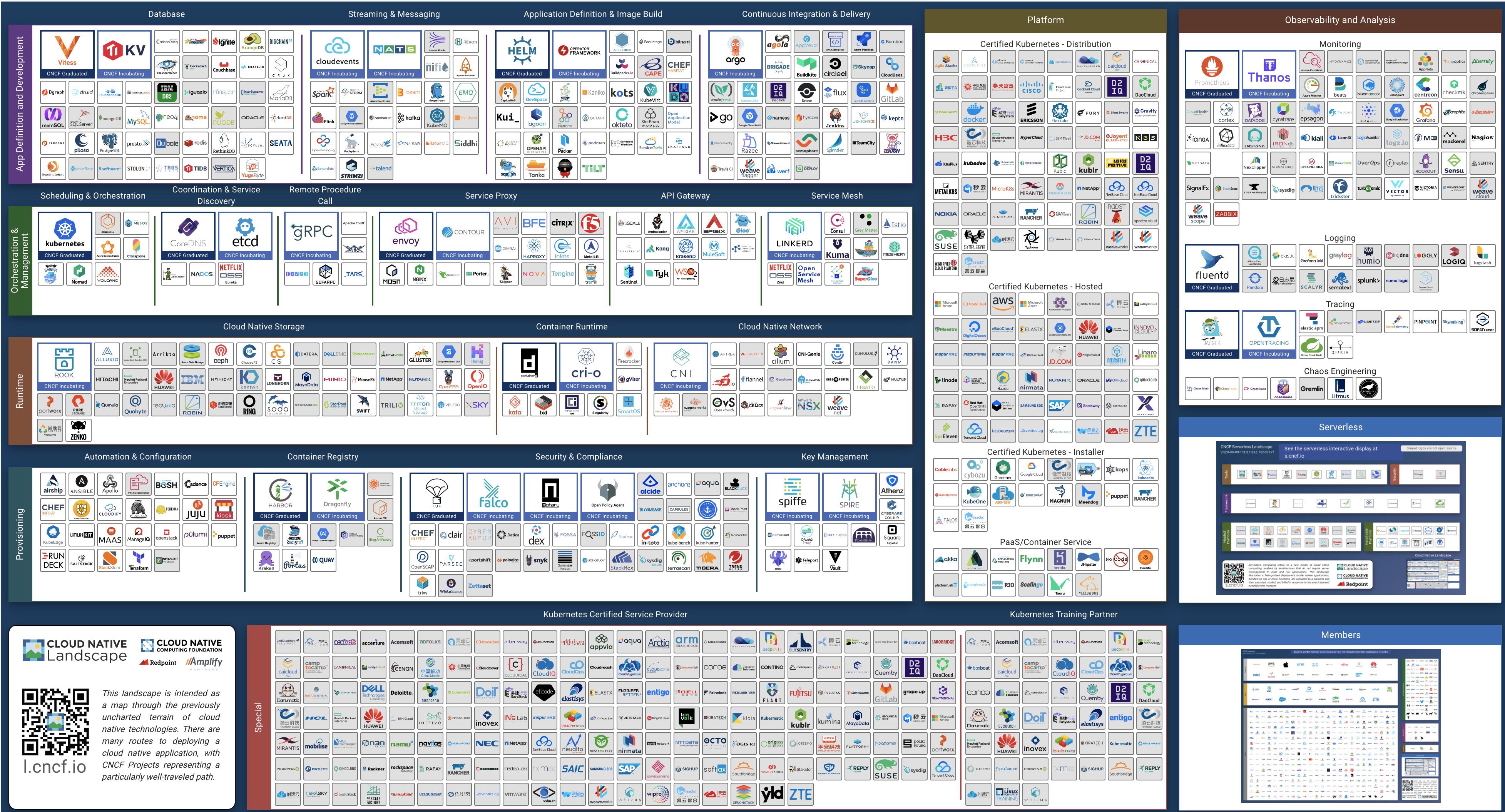

As an example, let’s consider everyone’s favorite overengineering punching bag: Kubernetes.

Kubernetes traces its conceptual lineage to Borg3, the cluster-management system that’s run Google’s production workloads for over a dozen years. The main value that Borg provides to Alphabet is its ability to maximize the capital efficiency of their datacenters. The technology that we now call “container orchestration” allowed them to get more computing oomph out of their fleet by maximizing utilization and making more efficient use of machines they’d already paid for.

Is maximizing capital efficiency of your datacenter or cloud environment a concern for your company? If you believe Kubernetes offers other benefits4, are you confident that they outweigh the complexity and maintenance overhead?

I find this thought process helpful when evaluating new tools, patterns, frameworks, or management practices. Conventional wisdom advocates that you fully understand a problem before applying a solution to it. It’s also important to understand the conditions that led to a solution and how those conditions align with those you find yourself in.

Regardless of the decision you end up making, this process is likely to make you a better engineer. The job is fundamentally about building systems to solve problems at reasonable cost. That cost is measured not only as upfront capital expenditure, but in the ongoing drag associated with maintenance and cognitive load. More often than we realize, engineering is about right-sizing a solution in light of these ongoing costs.

Further reading

A few links to other reading material on related topics:

- Reality has a surprising amount of detail, by John Salvatier

- Learn to never be wrong, by Will Larson

- Choose Boring Technology, by Dan McKinley

- Synthesis over invention, by yours truly

- The concept of “integrative thinking”, as described in Roger Martin’s book, The Opposable Mind

Thanks to Parth Upadhyay, Ehsan Noursalehi, Wilhelm Bierbaum for reading and providing feedback on drafts of this essay.

- Not to be that guy, but for full disclosure, I've had two stints at Google/Alphabet in my career, first as a lowly intern in 2010 and more recently leading a software team on an early-stage project at X. ↩

- This research can often be done by reading blog posts or conference papers related to the technologies in question (major plug for The Morning Paper's digestible summaries of papers). Recorded conference talks can be good sources, too. If you are networking-inclined, nothing beats being able to hear from experienced people directly. ↩

- Or really, Omega. Long story. ↩

- Container orchestration tools are marketed as solutions for developer productivity and software scalability, which has always felt like revisionist history to me. In my understanding, these were not the primary concerns this technology was invented to address. ↩