Coordinating technological change in large software organizations

The topic of software scalability seems to bring out the armchair general in everybody. Much of the culture of the software industry is fueled by anecdotal war stories, blog posts, and “this one paper you should read”. We are all knee-deep in an unending stream of literature prescribing ways to achieve maximum computer performance, but the organizational consequences of hyper-growth get far fewer headlines. I would argue that these consequences have more of an impact on the daily lives of more developers than the scalability of code. The structure of a company can determine what you work on and who you do it with. Without widespread appreciation for the cost of coordinating technology changes across such a dispersed group of people, it’s hard to imagine any single employee not being impacted by wasted time and miscommunication.

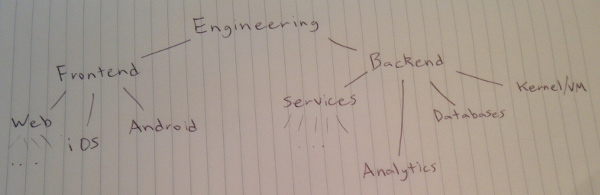

A common tactic for scaling a software engineering organization is to compartmentalize teams around various components that collectively make up the company’s product. The development team may be split into Frontend Engineering and Backend Engineering. Each of these may be subdivided into focus areas, terminating in teams that cover specific sets of technologies. In this manner, a company’s team structure is modelled as a tree (conveniently similar to how its personnel fit into a tree-based org chart):

For instance, “Backend Engineering” may encompass any piece of technology deeper in the stack than user-facing clients, from analytics pipelines and application servers down to databases and operating systems. This model is especially well-suited for the development of service-oriented architectures, in which the components of a product’s backend are encapsulated in network services each maintained by small teams.

The burden of coordination

A consequence of this organizational complexity is an increase in the amount of coordination required to make progress. Given the subdivision into specialized teams, any work to improve the overall product will necessarily involve multiple teams. For example, the task of adding a recommendations widget may spawn work for the web, iOS, and Android client teams, the creation of a new batch job to be built and maintained by the analytics team, and a new API endpoint to be added by an application services team. The burden imposed by this need for top-down, product-oriented coordination is part of what motivates the widespread criticism of “big companies”. Implicit in the idea of being an early employee at a growing company is the ability to be directly involved in the product. As a workforce grows, the perceived ability of any individual to affect change diminishes. Compared to the freedom and breadth enjoyed by employees of short-staffed small businesses, making an impact within a larger organization may seem like more trouble than it’s worth. This sentiment often manifests in technology-driven companies leaving a trail of “startup people” in their wake who step away from the company once it’s survived the trial by fire of early-stage growth.

However, well-run large organizations benefit from the higher throughput afforded by a larger workforce to apply to problems. A great example of this on a grand scale is Apple, whose ability to “walk and chew gum at the same time” results in concurrent efforts to drastically reshape both their mobile and desktop offerings.

This covers the macro-level work that trickles down from high-level product decisions, but not the variety that stems from changes deep in the stack. Infrastructure work results in a separate class of communication overhead.

Bottom-up coordination

The often underestimated counterpart of this top-down coordination is the cost of the bottom-up coordination imposed on developers working on infrastructure. By “infrastructure” I mean any technology that is depended upon by other developers. In this context, infrastructural work would include library development, database administration, and service ownership. For these kinds of teams, making profound changes implies effort to coordinate with numerous teams. For example, before migrating to a new database or replacing a deprecated library, the initiating team will have to communicate with many others. These scenarios inevitably cause friction with other teams, whether by imposing unplanned work on them or simply adding the operational risk of deploying new code.

Part of what distinguishes great infrastructure teams is a sense of empathy for those that depend on them. When attempting to move an organization forward with a new technology, such a team will reduce the barrier to entry by addressing any likely concerns and minimizing the amount of work that developers have to do to make the switch. By going the extra mile to ease the lives of others, the team initiating the change improves the likelihood of success and greases the wheels of forward progress.

Preventing surprises

When rolling out a new technology, the goal is to lessen the likelihood of something unexpected happening. This involves predicting and documenting the things that are unavoidably apt to change as a consequence of the new technology. To those without context, any change will be unexpected, so the main thing to strive for is increasing the organization’s collective awareness of the change without being annoying.

Thorough documentation can go a long way, whether it be on a wiki, an email, or whatever communication mechanism the company relies on. A good way to frame migration documentation is in terms of the deficiencies of the old way and how the new hotness will improve the situation. “We’re hitting the safe upper limit of how far we can scale Database Product X within budget and our testing shows that Database Product Y will suit our projected needs for the next year and save us n dollars per month.”

Part of this documentation’s purpose is to walk developers through the process of migrating their projects to the new hotness. This will vary depending on the type of migration. For instance, a library change would call for introductory background information, before/after code samples, and links to any relevant API reference documentation. It’s important to mention any operational effects the changes may have. For instance, if the new APIs entail different resource utilization rates (e.g. object allocation, TCP connection churn) or behavioral changes, then the documentation should include specific metrics to keep an eye on when deploying the new code.

Conclusion

Coordinating changes within large software organizations is a necessary evil. There are serious downsides to doing too little or too much, so keeping a manageable number of people informed is a balancing game. Given the definitionally wide reach of “infrastructure”, bottom-up coordination is a key part of introducing new technologies within an organization.

Thanks to Ruben Oanta and Johan Oskarsson for reading and providing feedback on drafts of this post.